GETTING READY FOR THE 1940 CENSUS: Searching without a Name Index

Stephen P. Morse

This article appeared in the Association of

Professional Genealogists Quarterly (December 2011).

Background

The US census has been taken every ten years starting in 1790. In 1942, all censuses up to and including the 1870 census were made available to the public. And since then, each census has been made available to the public 72 years after the census was taken (73 years in the case of the 1900 census). As of this writing (October 2011), the last census that has been made available is the 1930 census.

The pages of each of these censuses (with the exception of the 1890 census, most of which was destroyed due to a fire) have been scanned and placed online at various free and pay websites. And the names of all people in these censuses have been indexed, making it possible to search for people in the census by name.

Opening Day for the 1940 Census

The census day for the 1940 census was April 1, 1940. That doesn’t mean that the census taker knocked on the door on April 1 and took down the information. He probably came a few days after April 1. But the questions he asked pertained to April 1. Uncle Sam wanted to get a snapshot of the nation as it existed on April 1.

Since the census is sealed for 72 years, opening day for the 1940 census should be April 1, 2012. But it will be delayed to April 2 since April 1 falls on a Sunday, and the National Archives is closed on Sundays.

In previous years, the release of each census involved making microfilm copies of the master census microfilms (the original census pages have long since been destroyed). These microfilm copies were then made available to various archives and libraries. It was from these microfilm copies that several companies and organizations scanned the census images and placed them online.

That will not be the case for the 1940 census. The master microfilm will not be copied onto distribution microfilm. Instead it will be scanned and put directly online. That will make it available to anyone with Internet access on opening day. Furthermore, it will be accessible to all for free.

But a complete name index will not exist until at least six months (best guess at this time) after opening day. That means that the only way to access the census initially will be by location. However the census is not organized by address but rather by the Enumeration District (ED). So to access the census, you will need to obtain the Enumeration District of your desired location.

Enumeration Districts

An Enumeration District is an area that can be canvassed by a single census taker (enumerator) in a census period. Since 1880, all information in the census is arranged by Enumeration District. If you do not know the Enumeration District, you cannot access the census by location!

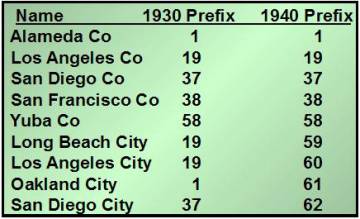

Each Enumeration District within a state has a unique number. In 1930 and 1940, the number consists of two parts, such as 31-1518. The first part is a prefix number assigned to each county (usually alphabetical) and the second part is a district number within the county. In 1940 (but not in 1930) some of the larger cities have their own prefix number. Such city prefix numbers come after the last county prefix.

As an example, in 1930 the prefixes in California went from 1 (Alameda County) to 58 (Yuba County). Los Angeles County was somewhere in the middle with prefix number 19. Long Beach City is in Los Angeles County, so in 1930 it too had prefix 19. But in 1940 it was given its own prefix, namely 59. It was followed by Los Angeles City (60), Oakland City (61) and San Diego City (62).

Now that you know what an Enumeration District is, you’ll need to know how to obtain the Enumeration District for the location you are interested in.

Where did the family live?

Before you can determine the family’s Enumeration District, you’ll have to know where they were located. If you don’t already have their address, here are several ways of finding it.

Address books

An old family address book might list the addresses not only of the family but of family friends as well.

Birth / Marriage / Death certificates

Often vital records give the address at which the family resided. A birth certificate might list the residence of the mother. If the birth was a home birth, the certificate would list the family’s residence as the location of the birth. A marriage license would usually list the address of both the bride and the groom. And a death certificate would give the last address of the deceased.

City directories

City directories are like phone books but without the phone numbers, and are a good source of addresses. They exist for many cities. Of course phone books themselves are another good source, but phones were still relatively rare back in 1940.

Diaries

Old diaries might list family addresses.

Employment Records

Employment records for members of the family will certainly have addresses on them.

Letters

If the family saved some old letters that they’ve received, that would of course have the family’s address on it.

Local Newspapers / Books

If the family was mentioned in the local newspaper or in a local book, it might give the family’s address.

Naturalization Records

A person’s naturalization record would list where the person was living.

Photographs

A photograph might have an address written on the back. If it is a picture of the front of the house the family lived in, it might show the house number. And the picture might show the street sign in the distance.

Relatives

Some of the older relatives of the family might recall where the family lived, or they might have some of the documents mentioned here that can help determine where they lived.

School / Church records

Such records will most likely include an address.

Scrapbooks

Old scrapbooks are certainly a good source of obtaining the family’s address.

Social Security Applications

Since social security started in 1936, there’s a good chance that some of the family members applied for social security cards in the years around 1940, and those application would list the address.

World War II Draft Registration

World War II registrations occurred in the first half of the 1940s, so the address listed on the registration would likely be the address that the family lived at in 1940.

Information on the Census

What can you expect to find in the census? For the most part, it will be the same sorts of things that you are probably familiar with from previous census years. That includes things like street and house number, house owned or rented, house value or monthly rent, name of each person in household, relation of each person to the head of household, sex, color or race, age, marital status, place of birth, citizenship, current occupation, and industry.

In addition, there were several new and interesting questions in 1940. Some examples are name of informant (so you can see if the information was provided by someone knowledgeable), highest school grade completed (to see if education level affected whether or not person had a job in this recessionary period), country of birth as of 1937 borders (because the borders of Europe were changing fast and furiously in 1940), place of residence in 1935 (to see how migratory the population was due to the recession and great dust bowl of the 1930s), and income.

Furthermore, sampling was used for the first time on the census. Those people who happened to fall on one of two designated lines on the page (out of a total of 40 lines) were asked about the birthplace of their parents, their mother tongue, whether they were a veteran and of which war, whether they had a social security card, and their usual occupation and industry. That last question differed from the current occupation/industry question asked of everybody, and was intended to see if the recession caused people to work at jobs other than what they were trained to do. And if the person sampled happened to be a married woman, she was asked if she was ever married before, her age at first marriage, and number of children born alive.

There were many more questions that were considered for the census but were rejected. Examples of some of the rejected questions are whether you owned a bible, whether you are over six feet tall, your hair color, whether you owned a burial plot, and how many dogs you had.

The Tutorial Quiz,

or what do Donald Duck, Superboy, ET, and Rockefeller have in common?

The largest collection of tools for converting location information to Enumeration District is found on the One-Step website (http://stevemorse.org). And they are all free. But the number of census tools found there can be daunting. To simplify things, a Tutorial Quiz was developed whereby you will be asked a sequence of questions, and based on your answers you will be directed to the most appropriate One-Step tool or tools for your situation. The Tutorial Quiz is another tool on the One-Step website.

If you indicate that the family you are looking for lived in a large urban area, you will probably be directed to the One-Step Large City ED Finder. If they lived in a rural area, you will probably be directed to the One-Step ED Definition Tool. If the family hadn’t moved since 1930 and you know the 1930 ED, you will probably be directed to the One-Step 1930 / 1940 ED Converter.

In addition, you might be directed to other One-Step resources for a second opinion to make sure that the ED number that you found is correct. Some of these additional resources include the One-Step Census Tracts Tool, the One-Step ED descriptions as appearing on the NARA microfilms, the One-Step ED Street List Tool, the One-Step ED Maps Tool, the One-Step Changed-Street-Names Tool, and the One-Step Census Image tool.

Let’s look at some specific examples using the Tutorial Quiz. It will be shown as a dialog between you and the computer.

Example 1: Donald Duck

Computer:

Do you know where your family lived on April 1, 1940?

You:

I have no idea

Computer:

Look for any of the following:

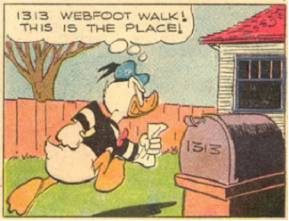

At this point the computer will present you with a list of sources for finding the address. These sources were discussed in a previous section. One of the items on the list is “local newspapers / books.” Well for Donald there are lots of books – comic books that is. And in the March 1954 issue of “Uncle Scrooge” is a story titled “Secrets of Atlantis.” That story shows Donald going to his house at 1313 Webfoot Walk in Duckburg Calisota. If Donald didn’t move around too often, there’s a good chance he will be at that address in 1940.

So Donald had the mystical house number of 1313. He was in good company, sharing that house number with none other than the Munsters at 1313 Mockingbird Lane, the new Addams family at 1313 Cemetery Lane, the Life of Riley at 1313 Blueview Terrace, and, most importantly, the writer of this paper (and that’s not a joke).

Note above that we cited our source for obtaining Donalds’s address. It is important to do so when obtaining genealogical information so that others can check on your work and make sure that you didn’t overlook anything.

Continuing with the quiz:

Computer:

Did that help?

You:

Yes, now I have the address

Computer:

What kind of an area did they live in?

You:

A large urban area

Duckburg was indeed large. According to Wikipedia, it had a population of around 300,000, but of course many of the inhabitants were anthropomorphized animals.

Computer:

Use the One-Step Large City ED Finder

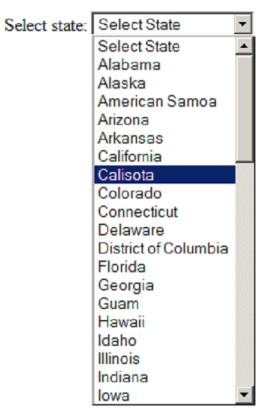

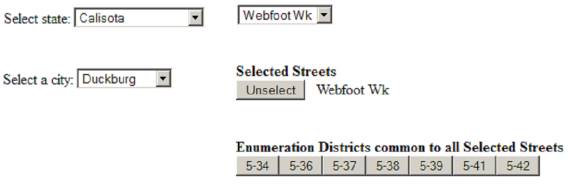

Now go to the Large City Enumeration District Finder and select the state of Calisota. That’s a fictional Disney state of course, and is a cross between California and Minnesota.

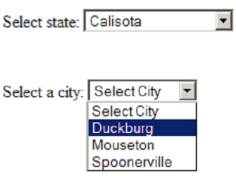

After selecting Calisota, a list of the cities in Calisota appears. Select Duckburg.

Upon selecting Duckburg, a list of the streets in Duckburg appears. Select Webfoot Walk.

At this point a list of Enumeration Districts appears – these are the Enumeration Districts that Webfoot Walk passes through. And the instructions say to select a cross street in order to narrow down the list of potential Enumeration Districts. A map of Duckburg shows that 1313 Webfoot Walk is at the corner of Webfoot and Quack. So select Quack Street, and the list of Enumeration Districts is reduced to just one – namely 5-38.

Now that you have the Enumeration District, you are ready to view the census images for that district. There’s a One-Step Census Image tool that lets you do that of course! You start at the first page of the Enumeration District and look at the left margin for Webfoot Walk. Keep going, page by page, until you find it. Then look in the next column for 1313. When you find that, you will have Donald’s census record.

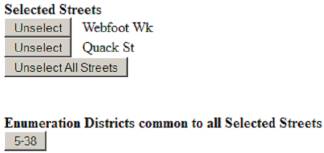

The 1940 census has not yet been made public, so I shouldn’t be showing you any of the information that is in it. But it seems innocent enough for me to show you Donald’s record, although I must ask you not to tell anyone that I’ve shown it to you. Here it is:

Note that Donald is the head of household, and he is living with his concubine Daisy (no, they never got married) and his three nephews. There is a circled X next to Donald’s name. That indicates that he was the informant. Donald rented the house, and his rent was $25 a month.

Example 2: Superboy

We all know that Superboy lived in Smallville, but I wonder how many know that Smallville is in Kansas.

©The CW Television Network

Computer:

Do you know where your family lived in 1940?

You:

Yes, in Smallville Kansas

Computer:

What kind of an area did they live in?

You:

A rural area

Computer:

Use the One-Step ED Definition tool

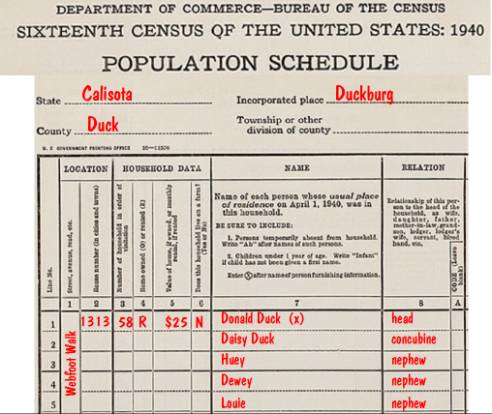

So go to the One-Step ED Definition tool, select the state of Kansas, and enter Smallville as a keyword to be searched for.

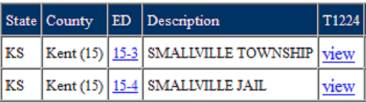

This will result in a search of the definitions of all the EDs in Kansas, looking for any that contains the keyword Smallville. There are two such EDs.

We can assume that Superboy was not living in the Smallville Jail, so that narrows it down to ED 15-3.

Example 3: Uncle Harry

Next let’s find Uncle Harry in the 1940 census. Harry lived in Roswell New Mexico. In fact, Harry was an illegal alien. He entered the country by flying in, using a saucer-shaped flying machine. He lived in the same home in Roswell for many years, and he flew in and out many times. But in 1947 he had a tragic accident -- his flying machine crashed at what is known as area 51, and Uncle Harry was killed.

Computer:

Do you know where your family lived on April 1, 1940?

You:

Yes, in Roswell New Mexico

Did

the family move between 1930 and 1940?

You:

No

Computer:

Do you have the 1930 ED number?

You:

No

Computer:

Do you have the 1930 census record?

You:

Yes

Computer:

Do you see the ED in the upper right-hand corner?

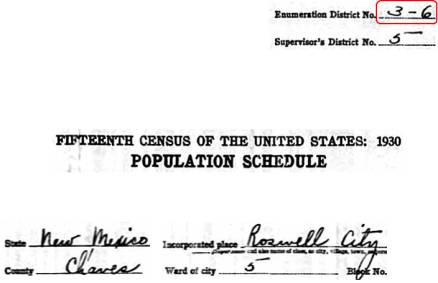

At this point you need to access the 1930 census record.

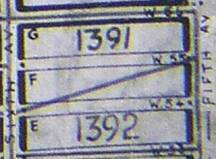

And there, in the upper right-hand corner is the ED, just where the computer said it would be. It’s Enumeration District 3-6.

Computer:

Do you see the ED in the upper right-hand corner?

You:

Yes

Computer: Use the 1930 / 1940 ED Converter!

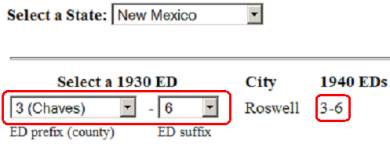

The ED converter takes a 1930 ED as input, and shows which 1940 ED or EDs cover the same area.

Note that the 1930 ED and 1940 ED are the same in this case – namely 3-6. That will often be true for rural areas in which there were not many changes. But it will not be the case for large cities, as shown in the next example.

Example 4: John D Rockefeller, Jr.

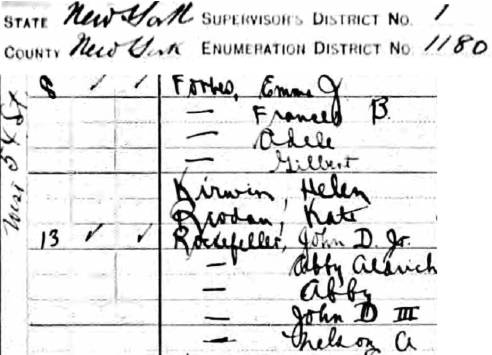

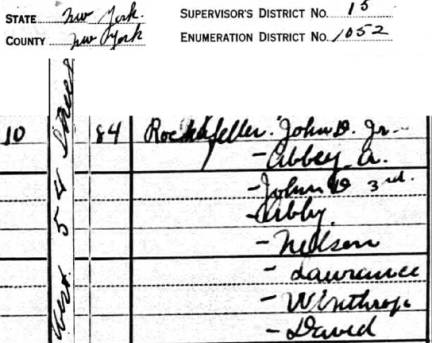

I have traced the Rockefeller family through the census from 1910 to 1930. In 1910 John Jr. lived with his family at 13 West 54th Street, Manhattan, and that was in ED 1180. However this address is suspicious since it follows 8 West 54th Street. We would have expected the census taker to do several houses on the same side of the street, so following 8 should probably be 10 and not 13.

1910

Census

In 1920 John Jr. was at 10 West 54th Street, and that was in ED 1052. The fact that the ED changed is not surprising, since the EDs in large cities were completely renumbered for each census.

1920

Census

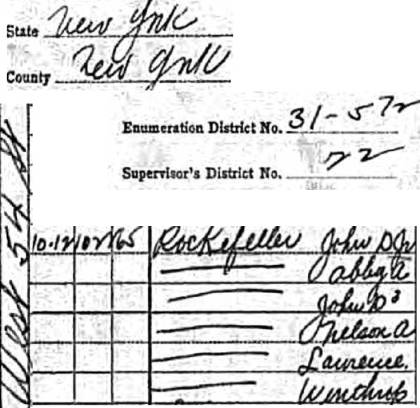

In 1930 he was at 10-12 West 54th Street, and the ED was 31-572. If our suspicions about the 1910 census are correct and the house number really was 10 and not 13, John Jr has been in the same house from 1910 to 1930.

1930

Census

So there is good reason to believe that he would be at the same address in 1940.

Computer:

Has the family moved since 1930?

You:

No

Computer:

Do you have the 1930 census record?

You;

Yes

Computer:

Do you see the ED in the upper right-hand corner?

You:

Yes

Computer:

Use the 1930 / 1940 ED Converter!

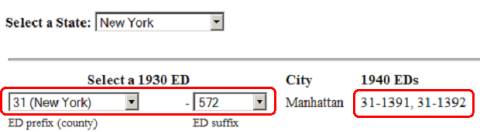

Enter 31-572 as the 1930 ED, and the One-Step ED Converter shows that the ED in 1940 is either 31-1391 or 31-1392.

Review

That covers a lot of ground, so it is time for a review. Here are the major One-Step tools for determining EDs in the 1940 census, and the situations in which you would use each one.

- Large Cities: Use the One-Step Large City ED Finder

- Rural Areas: Use the One-Step ED Definition tool

- Know 1930 ED: Use the One- Step ED Converter tool

It’s not quite that simple, and the Tutorial Quiz will guide you through some of the subtleties.

Other Resources (Second Opinions)

Before running to view the census images, it would be a good idea to verify that the ED found is indeed correct. It could take a considerable amount of time to step through every page of an ED looking for the family, and it would be a shame to go through an entire ED only to later learn that it was the wrong ED.

So let’s look at some examples of getting a second opinion.

Example 5: John D Rockefeller, Jr again

Computer:

Congratulations, you’ve found your ED.

Would you like a second opinion?

You:

Yes

Computer:

Use the One-Step Census Tracts tool!

Many cities are broken up into census tracts. These tracts provide stable geographic units for the presentation of statistical data across census years. For our purposes, we can use the tracts as an aid for determining the Enumeration District because the ED definitions usually include tract numbers.

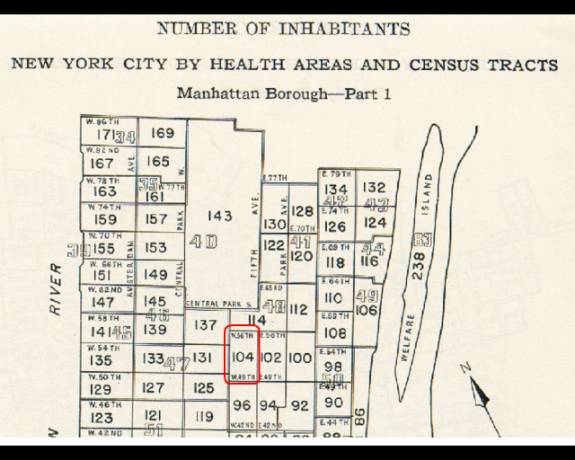

The tract for John D Rockefeller, Jr. can be obtained by using the One-Step Census Tracts tool. That tool will bring up the census tract map for Manhattan. And that map shows that Rockefeller lived in census tract 104.

Computer:

Use the One-Step Census Tracts tool!

You:

Got it. It’s census tract 104

Computer:

Enter that into the One-Step ED Definition Tool.

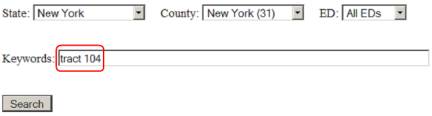

So enter “tract 104” as a keyword in the One-Step ED Definition tool and do the search.

The results show that there are four EDs in tract 104, namely 31-831, 31-832, 31-833, and 31-834. The latter two were the two EDs obtained previously. This confirms that those EDs are valid candidates.

But it would be nice to narrow it down to a single ED. So continue with the quiz and see if there is another second opinion.

Computer:

Would you like another second opinion?

You:

Yes

Computer:

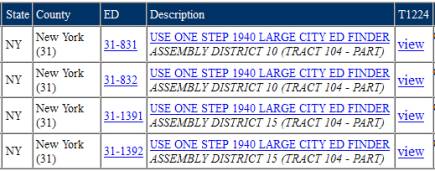

Go back to the One-Step ED Definition tool and click on link to view T1224

Doing so brings up the ED definition found on NARA microfilm series T1224, which is sometimes more complete than the abbreviated description displayed by the One-Step ED Definition tool.

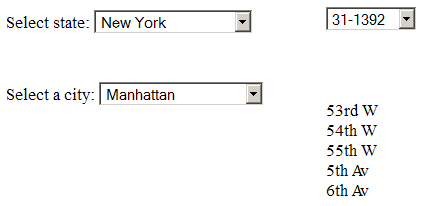

These descriptions indicate that each of the two EDs includes a part of the city block bounded by W 54th Street, 5th Avenue, W 55th Street, and 6th Avenue That block is split by a diagonal line into two triangles, with one triangle in each ED. The triangle with W 54th Street belongs to ED 31-1392. So the desired ED is 31-1392.

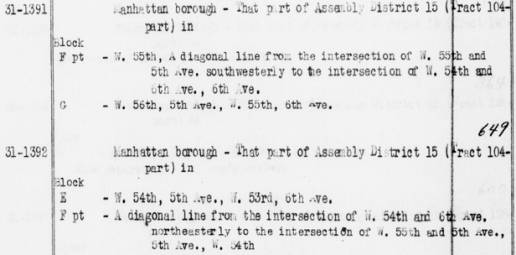

But that description was very hard to follow. An easier way to see this would be from an ED map of the area. Another tool on the One-Step website lets us look at the maps for the various EDs. So use the One-Step ED Maps tool to bring up the map image that contains the two EDs in question.

Wanted still more confirmation? Another tool on the One-Step website shows the streets in any ED in a large city. It is the One-Step ED Street List tool. Applying that tool to ED 31-1392 in New York gives the following:

Street Missing

The One-Step tools for dealing with large cities involve selecting specific streets from a list of streets. But sometimes the desired streets or cross-streets are not in the list.. That’s because the cross-streets might have been determined by using contemporary maps of the area whereas the streets listed in the One-Step tools are the streets that were there in 1940. Sometimes streets change names over the years, sometimes they no longer exist, and sometimes house numbers change. To help in such situations, there is a One-Step tool that deals with changed street names and changed house numbers. It consists of a list of about 250 cities, and shows the old street names and the corresponding new names for each.

Search by Name

After a while a name index will be produced for the 1940 census, and when that happens it will be much simpler to find people in that census. Two questions come to mind when a 1940 name index becomes available:

1. Will the One-Step website support the 1940 name index?

The One-Step site contains a search form for searching for people in prior census years, and that form will be expanded to include 1940 as well. The One-Step name search will involve accessing the name index on other websites, so you might wonder why you shouldn’t simply go to those websites directly. That’s because the One-Step search form will include features not found when you go to the underlying site directly.

One example is that there is a single One-Step name search form that lets you search in any particular year. Suppose you have just found your ancestor in the 1920 census and now want to search for him in the 1930 census. His name hasn’t changed. His year and place of birth haven’t changed. And he probably has other attributes that have remained the same from one census year to the next. Yet from many of the commercial sites that have a search-by-name capability, you are required to leave the 1920 search form, go up several levels through their site to get out of 1920, then come down several level in 1930 before you get to their 1930 search form. Then you have to enter your information again. From the One-Step search-by-name form you simply change the year, which is one of the fields on the form, and repeat the search with all the other values left in tact.

There are more advantages to using the One-Step name-search form. It will probably contain more search fields than will be found on the underlying websites (it already has more fields for the earlier census years). Another advantage is that the One-Step site will provide name search and location search all on the same site. And there will probably be other advantages as well.

2. Will the One-Step 1940 location tools become obsolete?

The One-Step site contains location tools for the years 1900 to 1930, and these are not obsolete even though name indexes exist for these years. And the reason the location tools are not obsolete is because not everyone can be found by doing a name search. To understand why, consider the way the census takers did their job.

The census taker arrived at your ancestor’s door with his census book in hand. He didn’t say “Here is the census book, please write your name in it.” Instead he probably said that the book was government property, and not only couldn’t your ancestor write in it, he couldn’t even look at it. That was because the book contained confidential information on his neighbors. So the census taker asked your ancestor to say his name and the census taker would write it down. Your ancestor might have been an immigrant who spoke with a thick accent. In that case, the census taker would take his best guess as to what your ancestor said, and he would write down what he thought he heard. Seventy two years later, commercial websites are going to create a name index. They will do so by having transcribers read the census records and type in what the census takers wrote down. The census takers were not known for having excellent handwritings. So the transcriber will need to make his best guesses as to what the census taker wrote down, which would be the census taker’s best guess as to what your ancestor said.

However it’s not as bleak as all that, and in most cases there will be no trouble doing a name search. But there will be a non-insignificant number of cases in which it will not be possible to find a person by name, and in those cases the location tools will still be necessary.

Moral

.

There’s more than one way to skin a cat. The trick is to try several of the One-Step tools and see if you get the same ED. The Tutorial Quiz can help determine a strategy.

Here’s the One-Step toolbox of 1940 census tools.

- One-Step Large City ED Finder

- One-Step ED Definition tool

- One-Step 1930 / 1940 ED Conversion tool

- One-Step Street List tool

- One-Step ED Maps tool

- One-Step Census Tract tool

- One-Step Street Name-Change tool

- One-Step Census Image tool

- One-Step Search-By-Name tool (available after name indexes become available)

And perhaps the most important is the One-Step Tutorial Quiz tool that will help you determine which of the above tools to use. And there is one more tool for those of you who want to just jump right in and not be bothered answering a lot of questions. That’s the One-Step Unified ED Finder tool, described in the next section.

A Unified Approach

So far you have been presented with the choice of figuring out which of the many One-Step ED tools is right for you, or of answering a series of questions that will help you determine which tool to use. But if you don’t have the time to do either of those, and simply want to enter your location and get the ED, then the One-Step Unified ED Finder is the tool you want. This unified tool provides access to the three most popular One-Step ED tools – namely the Large City ED Finder, the ED Definition tool, and the 1930/1940 Conversion tool. If the city you enter on the unified form is one of those supported by the Large City ED finder, it will take you directly to that tool with your state, city, street, and even house number prefilled. If you’ve entered a 1930 ED number on the unified form, it will take you directly to the results of the 1930/1940 ED conversion. And if neither of those apply, it will take you to the results that you would have gotten from the ED Definitions tool.

Expect the Unexpected

There are several anomalies in the 1940 census that were not present in previous census years. You’ll need to know about them so that you don’t get confused when searching in the census. These are the so-called Census Minute, and the Page Numbering gaps.

The Census Minute (or why am I not in the census?)

In previous years there was an enumeration day and a census day. The enumeration day was the day that the census taker knocked on your ancestor’s door. The census day (April 1) was the day to which your ancestor’s answers apply. A person born on April 1 was to be counted and one born on April 2 was not to be counted. Similarly a person who died on April 1 was to be counted, but one who died on March 31 was not to be counted.

In 1940 there was a census minute instead of a census day. That minute was 12:01 AM on April 1. A person born on April 1 but after 12:01 AM was not to be counted and will not appear in the census. In previous years, such a person would have appeared in the census.

The Numbering Gap (or why are so many pages missing?)

In previous years, all pages were numbered consecutively starting at 1A. The next page would be 1B, then 2A, then 2B, etc. If the census taker finished visiting all the homes in the district and went back to try to get people he might have missed, those people would appear on pages numbered immediately after the last page of the first set of visits. Since the census taker was being paid by the name, he was very motivated to find more people.

In 1940, his instructions were to start the second set of visits on page 61A, regardless of the page number on which the first set of visits ended. This assumes that the last page number of the first set of visits was less than 61A. Furthermore, on April 8th and 9th he was supposed to visit hotels and flop houses looking for transients, and those visits were to start on page 81A.

Assume that the first set of visits ended on page 40B. The second set of visits would start on 61A, and the pages from 41A to 60B will appear to be missing. But they aren’t missing – they never existed.

So just because we see these numbering gaps, we shouldn’t use them as an excuse for not being able to find our family in the census. True numbering gaps can be easily detected because each of the A pages (1A, 2A, etc) has a second number, which is stamped on the top rather than being handwritten. Those stamped numbers should not have any gaps.

What does NARA have to say?

The National Archives and Records Administration website (http://www.archives.gov/research/census/1940/) currently has a section on how to find people in the 1940 census. In that section are several references to the One-Step website. Specifically, on their main page on 1940 Census Records, in part 3 Finding Aids, they state “Find Census Enumeration Districts using Stephen P. Morse’s Search Engines” and they give a link to the One-Step site. And in their section on “What you can do now in preparation for the opening of the 1940 Census” they say “Use the Search Utilities at http://stevemorse.org/census/.”

Conclusion

On opening day for the 1940 census, April 2, 2012, there will be no name index. The only way to access the census will be by knowing the Enumeration District, and the easiest way to determine the Enumeration District will be by using the tools on the One-Step website (http://stevemorse.org). There is no charge for using the One-Step tools. So the One-Step website should be one of the first sites you visit on opening day.

Acknowledgement

None of the One-Step census tools would have been possible without the help of Joel Weintraub. He had the original idea of developing location tools for finding people in the 1930 census. He is also responsible for all of the tables used in all the One-Step census location tools. He developed many of the tables himself, and he supervised a team of volunteers to develop the remaining tables.