GETTING READY FOR THE 1950 CENSUS:

Searching With and Without a Name Index

Stephen P. Morse and Joel D. Weintraub

This article was written October 2019

This article is based on a similar article for the

1940 census that appeared in the

Association of Professional Genealogists Quarterly (December 2011).

Background

The US census has been taken every ten years starting in 1790. Since 1942, all censuses have been made available to the public 72 years after the census was taken (73 years in the case of the 1900 census). As of this writing (October 2019), the last census that has been made available is the 1940 census.

When the 1950 census is released in April 2022, it will not have a name index. So finding people in the census will involve searching by location instead. Even when a name index becomes available, there will still be many reasons for doing locational searches.

The census is organized by Enumeration Districts (EDs), so the location needs to be converted to an ED before the census can be accessed. The One-Step website (https://stevemorse.org) contains numerous tools for obtaining EDs. This paper will present the various tools and show circumstances in which each can be used.

Note that there are several parts (called schedules) of the census. There is the population schedule, the housing schedule, the agricultural schedule, etc. Unless noted otherwise, the term census used in this paper refers to the population schedule.

The 72-year Rule, Fact and Fiction

The census is sealed

for 72 years because of life expectancy.

That statement, although widely believed, is not true. We need to look at the history of the census

to find out why the 72-year rule exists.

From 1790 to 1870 each

census was made available immediately after it was taken. One copy of the census was typically sent to

the Washington for archival purposes. A

second copy was typically sent to the various local courthouses for all to

see. Of course all they could see was

the census for that local area. In order

to see the census for the entire country they would have to travel from

courthouse to courthouse.

From 1880 to 1940

there was only one copy of each census and it was sent to the Census Bureau and

was kept closed to the public.

Statistical data about the census was released to the general public,

but not the information about individual people in the census.

In 1934 the National

Archives was formed, and in 1942 the Census Bureau transferred most of the census

records to the National Archives. The

National Archives decided to open all censuses up to and including 1870. This established a de facto 72-year rule.

In 1952 the Census

Bureau transferred the 1950 census to the National Archives under the condition

that all censuses remained sealed for 72 years.

With that agreement, the 1880 census was released and the 72-year rule

was now well established.

One exception was

the 1900 census, which was sealed for 73 years.

There were privacy concerns raised in 1970 during the enumeration of the

1970 census, and that caused the Census Bureau to reverse its decision about

releasing the census pages. As a result,

the National Archives held up the release of the 1900 census, scheduled for

1972, until they received a ruling from the U.S. Attorney General. A compromise was reached in 1973 and the 1900

census was then opened.

Opening Day for the 1950 Census

The census day for the 1950 census was April 1, 1950. That doesn’t mean that the census taker knocked on the door on April 1 and took down the information. He might have come anytime during the month of April. But the questions he asked pertained to April 1. Uncle Sam wanted to get a snapshot of the nation as it existed on April 1. Since the census is sealed for 72 years, opening day for the 1950 census will be April 1, 2022.

Prior to the 1940 census, the release of each census involved making microfilm copies of the master census microfilms (the original census pages have long since been destroyed). These microfilm copies were then made available to various archives and libraries. It was from these microfilm copies that several companies and organizations scanned the census images and placed them online.

That was not the case for the 1940 census. Instead scans of the 1940 microfilms were put directly online, making it available to anyone with Internet access on opening day. Furthermore it was accessible to all for free. It is anticipated that the same will be true for the 1950 census.

But a complete name index for the 1950 census will not exist until at least six months (best guess at this time) after opening day. That means that the only way to access the 1950 census initially will be by location. However the 1950 census is not organized by address but rather by the Enumeration District. To access the census, we need to obtain the Enumeration Districts of our desired locations.

Enumeration Districts

An Enumeration District (ED) is an area that can be canvassed by a single census taker (enumerator) in a census period. Since 1880, all information in the census is arranged by ED. If we do not know the ED, we cannot access the census by location!

Each ED within a state has a unique number. Starting in 1930, the number consists of two parts, such as 31-1518. The first part is a prefix number assigned to each county (usually alphabetical) and the second part is a district number within the county. Starting in 1940 the large cities were given their own prefix number. Such city prefix numbers come after the last county prefix and the cities are in alphabetical order. A large city in 1940 was a city with a population of 100,000 or more. In 1950 it was 50,000 or more.

As an example, the number of counties in California is currently 58, and has been so since 1907. The county prefixes go from 1 (Alameda County) to 58 (Yuba County). And those were the only prefixes in 1930. In 1940 the following four cities were given their own prefixes: Long Beach, Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego. In 1950 another 13 cities were elevated to having their own prefix. This is illustrated in the chart below. For brevity, not all counties are included in this chart. A red entry in the chart indicates a city with its own prefix.

|

|

To read this chart, note that Los Angeles County is somewhere in the middle of the county list and has a prefix of 19. Long Beach City is in Los Angeles County, so in 1930 it too had prefix 19. But in 1940 it was given its own prefix, namely 59. And in 1950 its prefix became 65 due to the addition of more cities with their own prefix.

Now that we know what an ED is, we need to know how to obtain the ED of the locations we are interested in.

Where Did the Family Live?

Before we can determine the family’s ED, we have to know where they were located. If we don’t already have their address, here are several ways of finding it.

Address Books

An old family address book might list the addresses not only of the family but of family friends as well.

Birth / Marriage / Death Certificates

Often vital records give the address at which the family resided. A birth certificate might list the residence of the mother. If the birth was a home birth, the certificate would list the family’s residence as the location of the birth. A marriage license would usually list the address of both the bride and the groom. And a death certificate would give the last address of the deceased.

City Directories and Phone Books

City directories are like phone books but without the phone numbers, and are a good source of addresses. They exist for many cities. Of course phone books themselves are another good source.

Diaries

Old diaries might list family addresses.

Employment Records

Employment records for members of the family will certainly have addresses on them.

Letters

If the family saved some old letters that they’ve received, that would of course have the family’s address on it.

Local Newspapers / Books

If the family was mentioned in the local newspaper or in a local book, it might give the family’s address.

Naturalization Records

A person’s naturalization record would list where the person was living.

Photographs

A photograph might have an address written on the back. If it is a picture of the front of the house the family lived in, it might show the house number. And the picture might show the street sign in the distance.

Relatives

Some of the older relatives of the family might recall where the family lived, or they might have some of the documents mentioned here that can help determine where they lived.

School / Church Records

Such records will most likely include an address.

Scrapbooks

Old scrapbooks are certainly a good source of obtaining the family’s address.

Social Security Applications

There’s a good chance that some of the family members applied for social security cards in the years around 1950, and those application would list the address.

World War II Draft Registration

World War II registrations occurred in the 1940s, so the address listed on the registration might be the address that the family lived at in 1950.

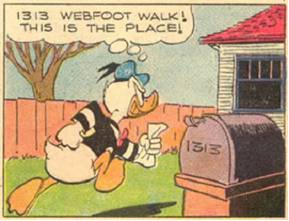

Example 1: Finding

Donald Duck in the 1950 Census

The largest collection of tools for converting location information to ED is found on the One-Step website (http://stevemorse.org). And they are all free. The main tool is the One-Step Unified ED Finder. That tool consolidates the functions of many of the other tools and in most cases is the only tool needed.

Let's illustrate the use of the Unified ED Finder by looking for Donald Duck in the 1950 census. We will need to know Donald's address before we can proceed further. We already saw the various places that we can look to obtain the address, and one of them was "Local Newspapers / Books." Well for Donald there are lots of books – comic books that is. And in the March 1954 issue of “Uncle Scrooge” is a story titled “Secrets of Atlantis.” That story shows Donald going to his house at 1313 Webfoot Walk in Duckburg Calisota. If Donald didn’t move around too often, there’s a good chance he was at that address in 1950.

So Donald had the mystical house number of 1313. He was in good company, sharing that house number with none other than the Munsters at 1313 Mockingbird Lane, the new Addams family at 1313 Cemetery Lane, the Life of Riley at 1313 Blueview Terrace, and, most importantly, one of the authors of this paper (and that’s not a joke).

Note above that we cited our source for obtaining Donald’s address. It is important to do so when obtaining genealogical information so that others can check on our work and make sure that we didn’t overlook anything.

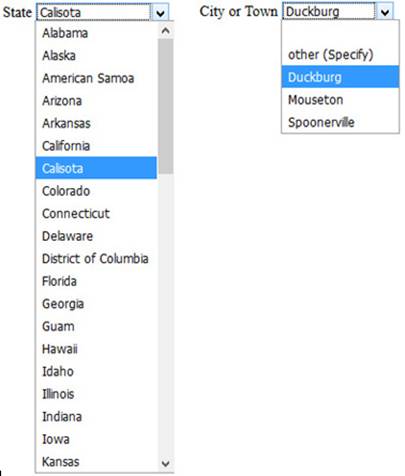

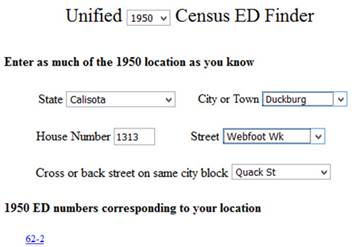

Next we go to the Unified ED Finder and select the year (1950) and the state (Calisota). That’s a fictional Disney state of course, and is a cross between California and Minnesota. After selecting Calisota, a list of some of the large cities in Calisota appears. Duckburg was indeed a large city according to Wikipedia, which at one time reported it as having a population of 300,000. Of course most of the populace were anthropomorphized animals. So Duckburg is on the list, and we will select it.

Upon selecting Duckburg, a list of the streets in Duckburg appears. We select Webfoot Walk. At this point a list of EDs appears – these are the EDs that Webfoot Walk passes through. And the instructions say to select a cross street in order to narrow down the list of potential EDs. A map of Duckburg shows that 1313 Webfoot Walk is at the corner of Webfoot and Quack. So we select Quack Street, and the list of EDs is reduced to just one – namely 62-2.

Now that we have the ED, we are ready to view the census images for that district. After April 1, 2022 there will be a One-Step Census Image tool that will let us do that of course! We would start at the first page of the ED and look at the left margin for Webfoot Walk. We keep going, page by page, until we find it. We then look in the next column for 1313. When we find that, we will have Donald’s census record.

The 1950 census has not yet been made public, so I shouldn’t be showing you any of the information that is in it. But it seems innocent enough for me to show you Donald’s record, although I must ask you not to tell anyone that I’ve shown it to you. Here it is:

The record shows that Donald is the head of household, and he is living with his concubine Daisy (no, they never got married) and his three nephews.

Note that one of the nephews falls on a line that is indicated as being a sample line. That means that more questions will be asked of him. Let's see what sampling is all about.

Sampling in the

Census

Sampling started with the 1940 census. Before that everybody was asked every question and nobody was singled out for extra scrutiny. In 1940 there were 80 lines on each sheet (including front and back), and the people on four of those lines (5%) were singled out for sampling. In 1950 six lines out of the 30 on each sheet (20%) were singled out for sampling. And the person on one of those 6 sampling lines was singled out for additional sampling.

The sampling lines were not the same on every sheet. In both 1940 and 1950 there were five different styles, each with a different designation for the sampling lines. In 1940, the same style was used on every sheet within an ED so as not to confuse the enumerator. This appears not to be the case in 1950 (according to the Enumerator's Reference Manual) and they did use different sampling styles within an ED just to confuse the enumerator. We won't know this for sure until we get to see the actual census pages.

The lines in the five different sampling styles in 1940 were:

lines 14, 29, 55, 68

lines 1, 5, 41, 75

lines 2, 6, 42, 77

lines 3, 39, 44, 79

lines 4, 40, 46, 80

In 1950 the lines were;

lines 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, 26

lines 2, 7, 12, 17, 22, 27

lines 3, 8, 13, 18, 23, 28

lines 4, 9, 14, 19, 24, 29

lines 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30

Information in the Census

What can we expect to find in the 1940 and 1950 censuses? For the most part, it will be the same sorts of things that we are probably familiar with from previous census years. That includes things like street and house number, name of each person in the household, relation of each person to the head of household, sex, color or race, age, marital status, etc. But there were several new questions and several questions that were dropped. The charts below show which questions were asked.

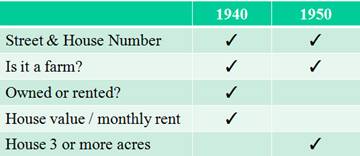

The following questions identifying the property were asked of the head of household

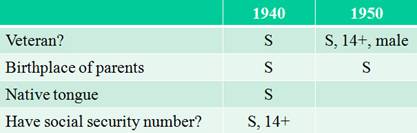

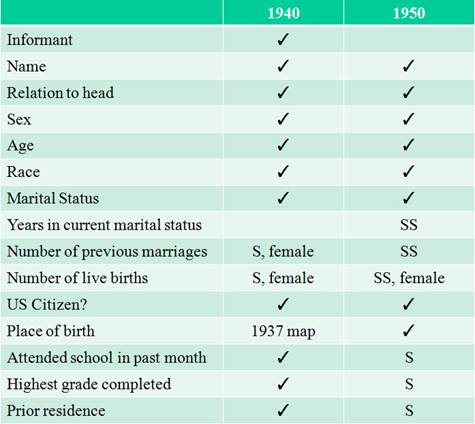

The following questions identified the person. An S indicates that the question was asked only on the sampling line. And an SS indicates that the question was asked on the extra-sampling line.

Designating the informant was done in 1940 for the first time. It proved to be very useful when the census was opened because it provided a means of assessing how reliable the answers might be. Unfortunately that designation was dropped in 1950.

Note the citizenship question in the chart above. The 1950 census was the last time that this question was asked.

In 1940 the borders of the countries in Europe were in a state of flux. So rather than ask the person for his country of birth based on a 1940 map, he was asked for his place of birth based on the map as it existed in 1937.

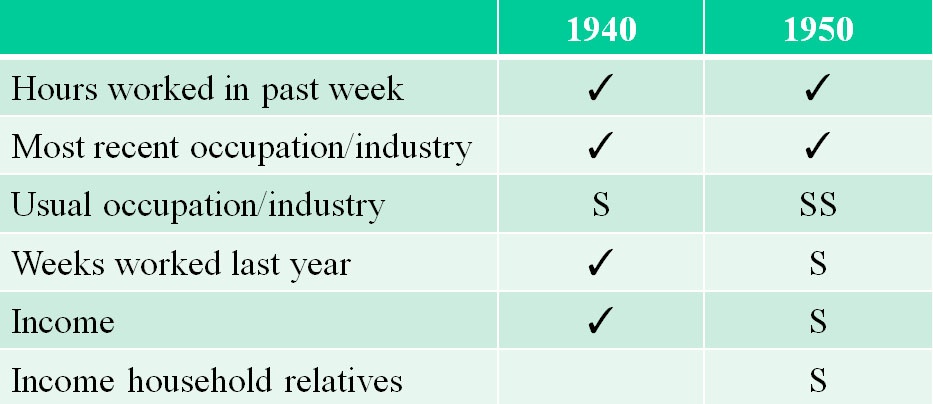

The following questions pertained to the line of work.

The income question in 1940 was very controversial and many people didn't want to answer it. In 1950 that question was moved to the sampling line.

There were many more questions that were considered for the 1940 census but were rejected. Examples of some of the rejected questions are whether you owned a bible, whether you are over six feet tall, your hair color, whether you owned a burial plot, and how many dogs you had. They were probably faced with similar rejected questions in 1950.

Example 2: Finding Superboy

in the 1950 Census

We all know that Superboy lived in Smallville, but I wonder how many know that Smallville is in Kansas.

©The CW Television Network

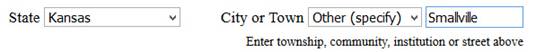

Smallville is a small town (obviously) so it was not likely to be one of those for which we generated street tables. The One-Step Unified ED Finder can still be used, but in this case select "Other" for the town and type in its name.

Once Smallville is typed in, a list of all the EDs in Kansas whose definition includes the word Smallville will be displayed.

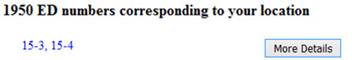

Pressing the More-Details button will show us the definitions of those EDs so we can make a determination as to which one is the most likely.

We can assume that Superboy was not living in the Smallville Jail, so that narrows it down to ED 15-3.

Example 3: Finding Uncle

Harry in the 1950 Census

Next let’s find Uncle Harry in the 1950 census. Harry and his wife lived in Roswell New Mexico. They were illegal aliens. They entered the country by flying in, using a saucer-shaped flying machine, and they would frequently take rides in it. In 1947 they had a tragic accident -- their flying machine crashed at what is known as area 51, and Harry's wife was killed. The army recovered her body but never returned it to the family. You've probably read about this as it was a major news story at the time.

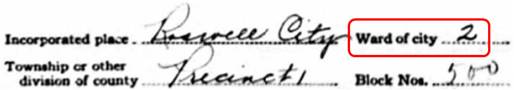

We don't know Harry's address in 1950 but we do have Harry's 1940 census record. It indicates a ward number, namely ward 2. Harry didn't move around much (he tried to remain under the radar) so he was probably in the same ward in 1950.

1940 Census

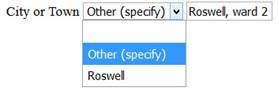

To find Harry's 1950 ED, we again use the Unified ED Finder and select "Other" for the city name even though Roswell is in the list of cities. That will allow us to type in the city name, and in this case we will type in "Roswell, ward 2". The Unified ED Finder will search the definitions of all EDs in New Mexico looking for any that specify Roswell, ward 2.

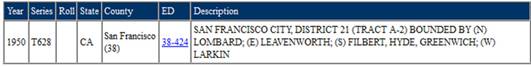

Example 4: The

Crookedest Street in the World

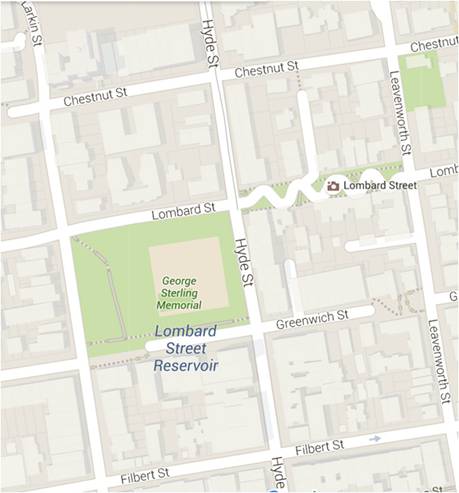

Lombard Street between Hyde Street and Leavenworth Street in San Francisco is affectionately referred to as the "Crookedest Street in the World." It's not really, and there is another street in San Francisco that is even crookeder (Vermont Street between 20th and 22nd Street), but it is not as well landscaped and so it has never become a tourist attraction.

Here is a map showing the crooked part of Lombard Street.

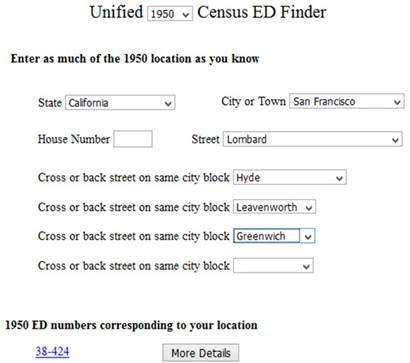

If we use the One-Step Unified ED Finder and enter Lombard Street and Leavenworth Street, we get three EDs. Adding Hyde Street reduces it to two EDs. That means that the two sides of Lombard were probably not in the same ED. Adding Greenwich as a back street should remove that ambiguity and get down to a single ED, and it does.

Other Resources (Second Opinions)

Before running to view the census images, it would be a good idea to verify that the ED found is indeed correct. It could take a considerable amount of time to step through every page of an ED looking for the family, and it would be a shame to go through an entire ED only to later learn that it was the wrong ED. There are some additional One-Step tools that can be used to verify the correctness of the found ED.

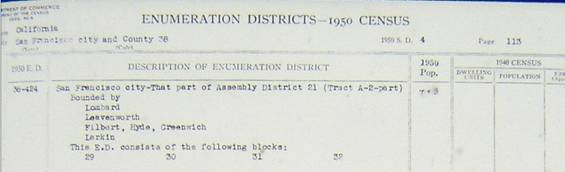

Transcribed ED

Definitions tool

Notice that there is a "More Details" button next to the ED in the screenshot above. Clicking on that button will bring up a One-Step tool that displays the transcribed definitions of the ED.

Microfilm ED

Definitions tool

There is another One-Step tool, namely one that displays the original ED definitions that appears on microfilm.

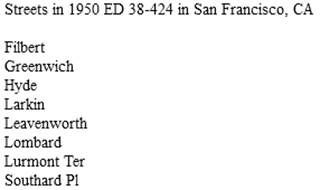

Street List tool

Another thing that would be useful is to obtain a list of all the streets within the ED. And there is a One-Step tool that does just that.

ED Map tool

Of course it would be useful to look at an ED map to determine the correct ED. And there is a One-Step tool that displays the ED map of a selected city. Here is a portion of that map for San Francisco, showing the boundaries of ED 38-424. For brevity, the map does not show the ED prefix.

Census Tract tool

Many cities are broken up into census tracts. These tracts provide stable geographic units for the presentation of statistical data across census years. For our purposes, we can use the tracts as an aid for determining the ED because the ED definitions usually include tract numbers.

The tract for the crooked part of Lombard Street can be obtained by using the One-Step Census Tracts tool. That tool will bring up the census tract map for San Francisco. And that map shows that the crooked street is in census tract A-2

.

.

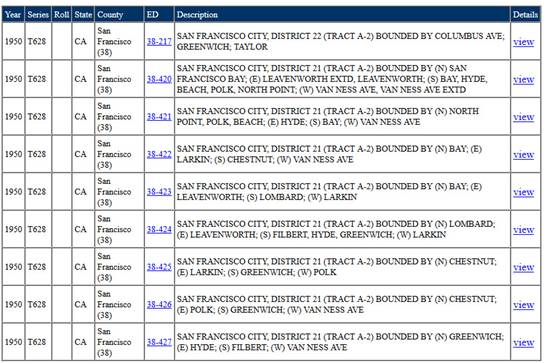

We can now return to the Unified ED Finder and type "San Francisco, tract a-2" for the city rather than selecting San Francisco from the list of cities. This will give us nine EDs, and if we ask for "More Details" about these EDs we get

From these details we see that the ED we want is 38-424.

Street Name-Change

tool

The One-Step tools for dealing with large cities involve selecting specific streets from a list of streets. But sometimes the desired streets or cross-streets are not in the list.. That’s because the cross-streets might have been determined by using contemporary maps of the area whereas the streets listed in the One-Step tools are the streets that were there in 1950. Sometimes streets change names over the years, sometimes they no longer exist, and sometimes house numbers change. To help in such situations, there is a One-Step tool that deals with changed street names and changed house numbers. It consists of a list of about 250 cities, and shows the old street names and the corresponding new names for each.

Tutorial Quiz

The

largest collection of tools for converting location information to Enumeration

District is found on the One-Step website (http://stevemorse.org). And they are all free. But the number of census tools found there

can be daunting. To simplify things, a

Tutorial Quiz was developed whereby you will be asked a sequence of questions,

and based on your answers you will be directed to the most appropriate One-Step

tool or tools for your situation. The

Tutorial Quiz is another tool on the One-Step website.

Searching the Census by Name

After a while a name index will be produced for the 1950 census, and when that happens it will be much simpler to find people in that census. Two questions come to mind when a 1950 name index becomes available:

1. Will the One-Step

website support the 1950 name index?

The One-Step site contains a form for searching for people in prior census years, and that form will be expanded to include 1950 as well. The One-Step name search will involve accessing the name index on other websites, so you might wonder why we don't simply go to those websites directly. That’s because the One-Step search form will include features not found on the underlying site.

An example of such a feature is that there is a single One-Step name search form that lets us search in any particular year. Suppose we have just found our ancestor in the 1920 census and now we want to search for him in the 1930 census. His name hasn’t changed. His year and place of birth haven’t changed. And he probably has other attributes that have remained the same from one census year to the next. Yet on many of the commercial sites that have a search-by-name capability, we are required to leave the 1920 search form, go up several levels through their site to get out of 1920, then come down several level in 1930 before we get to their 1930 search form. Then we have to enter our information again. From the One-Step search-by-name form we simply change the year, which is one of the fields on the form, and repeat the search with all the other values left intact.

There are more advantages to using the One-Step name-search form. It will probably contain more search fields than will be found on the underlying websites (it already has more fields for the earlier census years). Another advantage is that the One-Step site will provide name search and location search all on the same site. And there will probably be other advantages as well.

2. Will the One-Step

1950 location tools become obsolete?

The One-Step site contains location tools for the years 1880 to 1940, and these are not obsolete even though name indexes exist for these years. And the reason the location tools are not obsolete is because not everyone can be found by doing a name search. To understand why, consider the way the census takers did their job.

The census taker arrived at your ancestor’s door with his census book in hand. He didn’t say “Here is the census book, please write your name in it.” Instead he probably said that the book was government property, and not only couldn’t your ancestor write in it, he couldn’t even look at it. That was because the book contained confidential information about his neighbors. So the census taker asked your ancestor to say his name and the census taker would write it down. Your ancestor might have been an immigrant who spoke with a thick accent. In that case, the census taker would take his best guess as to what your ancestor said, and he would write down what he thought he heard. Seventy two years later, commercial websites are going to create a name index. They will do so by having transcribers read the census records and type in what the census takers wrote down. The census takers were not known for having excellent handwriting. So the transcriber will need to make his best guesses as to what the census taker wrote down, which would be the census taker’s best guess as to what your ancestor said.

However it’s not as bleak as all that, and in most cases there will be no trouble doing a name search. But there will be a not-insignificant number of cases in which it will not be possible to find a person by name, and in those cases the location tools will still be necessary.

Moral

There’s more than one way to skin a cat. The trick is to try several of the One-Step tools and see if we get the same ED.

Here’s the One-Step toolbox of 1950 census tools.

- One-Step Unified ED Finder tool

- One-Step ED Definition tool (transcribed along with augmented definitions)

- One-Step ED Definition tool (definitions on microfilm)

- One-Step Street List tool

- One-Step ED Maps tool

- One-Step Census Tract tool

- One-Step Street Name-Change tool

- Tutorial Quiz

- One-Step Census Image tool (available after the census is opened)

- One-Step Search-By-Name tool (available after name indexes become available)

Expect the Unexpected

There are several anomalies in the 1950 census that were not present in previous census years. We’ll need to know about them so that we don’t get confused when searching in the census.

A and B sheets

From 1880 to 1940 the census population schedules (what is typically referred to as "the census") were printed back to back. The front sheet was numbered with an A and the back sheet with a B. The numbering sequence was 1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, etc.

In 1950 the census population schedules and the census housing schedules were printed back to back. So there was no longer a need for the A or B indicators.

The Census Minute (or why am I not in the census?)

In previous years there was an enumeration day and a census day. The enumeration day was the day that the census taker knocked on your ancestor’s door. The census day (April 1) was the day to which your ancestor’s answers apply. A person born on April 1 was to be counted and one born on April 2 was not to be counted. Similarly a person who died on April 1 was to be counted, but one who died on March 31 was not to be counted.

In 1940 there was a census minute instead of a census day. That minute was 12:01 AM on April 1. A person born on April 1 but after 12:01 AM was not to be counted and will not appear in the census. In previous years, such a person would have appeared in the census.

In 1950 the census minute was abandoned. We are back to the census day again.

The Numbering Gap (or why are so many pages missing?)

Prior to 1940, all pages were numbered consecutively starting at 1A. The next page would be 1B, then 2A, then 2B, etc. If the census taker finished visiting all the homes in the district and went back to try to get people he might have missed, those people would appear on pages numbered immediately after the last page of the first set of visits. Since the census taker was being paid by the name, he was very motivated to find more people.

In 1940, his instructions were to start the second set of visits on page 61A, regardless of the page number on which the first set of visits ended. This assumes that the last page number of the first set of visits was less than 61A. Furthermore, on April 8th and 9th he was to visit hotels and flop houses looking for transients, and those visits were to start on page 81A.

Assume that the first set of visits ended on page 40B. The second set of visits would start on 61A, and the pages from 41A to 60B will appear to be missing. But they aren’t missing – they never existed.

So just because we see these numbering gaps, we shouldn’t use them as an excuse for not being able to find our family in the census. True numbering gaps can be easily detected because each of the A pages (1A, 2A, etc) has a second number, which is stamped on the top rather than being handwritten. Those stamped numbers should not have any gaps.

A similar situation existed in 1950 but the details are a bit different. Instead of the second visits starting on page 61A, they started on page 71. And the enumeration of transients was on April 11th and 13th instead of April 8th and 9th. Furthermore there is no designated page on which the transient enumerations are to appear. In fact, as of this writing it is not clear where those enumerations are located.

College Students

Before 1950, college students were enumerated at their parents' home, even though they were away at school when the census taker arrived. In 1950 they were enumerated at their college address. This is consistent with the general census rule:

"Each person should be enumerated at his usual place of residence."

Keep this in mind when looking for college students in the census.

What does NARA have to say?

The National Archives and Records Administration website (http://www.archives.gov/research/census/1940/) has a section on how to find people in the 1940 census. In that section are several references to the One-Step website. Specifically, on their main page on 1940 Census Records, in part 3 Finding Aids, they state “Find Census Enumeration Districts using Stephen P. Morse’s Search Engines” and they give a link to the One-Step site. And in their section on “What you can do now in preparation for the opening of the 1940 Census” they say “Use the Search Utilities at http://stevemorse.org/census/.”

As we get closer to the opening of the 1950 census, we assume that they will have similar references to the 1950 One-Step tools.

Conclusion

On opening day for the 1950 census, April 1, 2022, there will be no name index. The only way to access the census will be by knowing the ED, and the easiest way to determine the ED will be by using the tools on the One-Step website (http://stevemorse.org). There is no charge for using the One-Step tools. So the One-Step website should be one of the first sites you visit on opening day.

However you might be better off not waiting for opening day but rather obtaining your EDs from the One-Step site now. There will probably be an onrush of people coming to the One-Step site on opening day, slowing everything down. On the opening day of the 1940 census (back in 2012) there were over 2 1/4 million hits to the One-Step site.

Acknowledgement

I would like to acknowledge my co-author, Joel Weintraub, without whose help none of the One-Step census tools would have been possible. He had the original idea of developing location tools for finding people in the census. He is also responsible for all of the tables used in all the One-Step census location tools. He developed many of the tables himself, and he supervised a team of volunteers to develop the remaining ones.